When a Syrian prison guard tossed him into a dimly lit room, the inmate Abdo was surprised to find himself standing ankle deep in what appeared to be salt.

On that day in the winter of 2017, the terrified young man already had been locked up for two years in Syria's largest and most notorious prison, Saydnaya.

Having been largely deprived of salt all that time in his meagre prison rations, he brought a handful of the coarse white crystals to his mouth with relish.

Moments later came the second, grisly, surprise: as a barefoot Abdo was treading gingerly across the room, he stumbled on a corpse, emaciated and half buried in the salt.

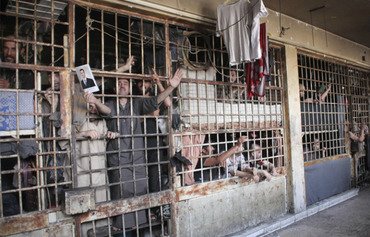

![Diab Serriya of The Association of Detainees and The Missing in Sednaya Prison views a page on the prison on the Amnesty International website at his office in Gaziantep, Turkey, on August 11. [Omar Haj Kadour/AFP]](/cnmi_am/images/2022/09/15/37121-saydnaya-prison-syria-600_384.jpg)

Diab Serriya of The Association of Detainees and The Missing in Sednaya Prison views a page on the prison on the Amnesty International website at his office in Gaziantep, Turkey, on August 11. [Omar Haj Kadour/AFP]

Abdo soon found another two bodies, partially dehydrated by the mineral.

He had been thrown into what inmates call "salt rooms" -- primitive mortuaries designed to preserve bodies in the absence of refrigerated morgues -- to keep up with the Syrian regime's industrial-scale prison killings.

The salt rooms are described in detail for the first time in an upcoming report by The Association of Detainees and The Missing in Sednaya Prison (ADMSP), which uses an alternate spelling of the prison's name.

AFP conducted additional research and interviews with former inmates.

Abdo, a man from Homs now aged 30 and living in eastern Lebanon, who asked that his real name be withheld, recounted the day he was thrown into the salt room, which served as his holding cell ahead of a military court hearing.

"My first thought was: may God have no mercy on them!" he said. "They have all this salt but don't put any in our food!

"Then I stepped on something cold. It was someone's leg."

'My heart died'

Up to 100,000 people have died in regime prisons since 2011, a fifth of the war's entire death toll, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

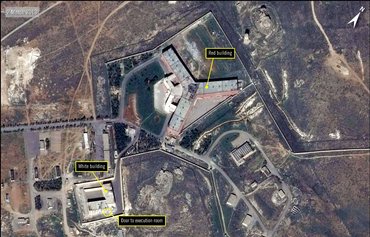

Abdo described the salt room on the first floor of the red building as a rectangle of roughly six by eight metres, with a rudimentary toilet in a corner.

"I thought this would be my fate: I would be executed and killed," he said, recalling how he curled up in a corner, crying and reciting verses from the Qur'an.

The guard eventually returned to escort him to the court. On his way out of the room, Abdo noticed a pile of body bags near the door.

He was released in 2020 but says the experience scarred him for life.

"This was the hardest thing I ever experienced," he said. "My heart died in Saydnaya."

About 30,000 people are thought to have been held at Saydnaya alone since the start of the conflict. Only 6,000 were released.

Most of the others are officially considered missing because death certificates rarely reach the families unless relatives pay an exorbitant bribe.

Another former inmate, Moatassem Abdel Sater, recounted a similar experience in 2014, in a different first-floor cell of about 20 sq metres, with no toilet.

Speaking at his new home in Reyhanli, Turkey, the 42-year-old recounted standing on a thick layer of the kind of salt used to de-ice roads.

"I looked to my right, and there were four or five bodies," he said.

"They looked a bit like me," Moatassem said, describing their skeletal limbs and scabies-covered skin. "They looked like they had been mummified."

He said he still wonders why he was taken to the makeshift mortuary, on the day of his release, May 27, 2014, but guessed "it might have been just to scare us".

Black hole

The ADMSP dates the opening of the first salt room in Saydnaya to 2013, one of the deadliest years in the conflict.

"We found that there were at least two salt rooms used for the bodies of those who died under torture, from sickness or hunger," group co-founder Diab Serriya said during an interview in Gaziantep, Turkey.

When a detainee died, Serriya said, his body would typically be left inside his cell with the other inmates for two to five days before being taken to a salt room.

The corpses remained there until there were enough of them for a truckload.

The next stop was a military hospital where death certificates -- often declaring a "heart attack" as the cause of death -- were issued, before mass burials.

The salt rooms were meant to "preserve the bodies, contain the stench... and protect the guards and prison staff from bacteria and infections", he said.

Former inmate Qais Murad recounted how, in 2013, he was called out of his cell to see his parents but on his way to the visitation area was shoved into a room.

Inside, he stepped on something like grit on the floor. Kneeling against the wall, he caught a glimpse of guards dumping about 10 bodies behind him.

When a cellmate returned from a visit later that day, his socks and pockets stuffed with salt, Murad understood what the substance was.

The ADMSP report is the most thorough study yet of the structure of Saydnaya, providing detailed schematics of the facility where thousands have died and of the division of duties among various army units and wardens.

"The regime wants Saydnaya to be a black hole; no one is allowed to know anything about it," Serriya said. "Our report denies them that."

![Former Saydnaya prison inmate Qais Murad, 36, re-enacts an episode from his treatment at his house in Gaziantep, Turkey, on August 11. [Omar Haj Kadour/AFP]](/cnmi_am/images/2022/09/15/37120-syria-former-inmate-600_384.jpg)