A new Amnesty International report that reveals the Syrian regime has executed 13,000 prisoners since 2011 presents further proof of the regime's brutality to those who oppose it, former detainees and human rights activists told Diyaruna.

In its February 7th report, "Human Slaughterhouse: Mass hangings and extermination at Saydnaya Prison, Syria", the international watchdog accuses the Syrian government of pursuing a "policy of extermination".

The report, based on the testimony of 84 witnesses, including former prison guards, prisoners and judges, reveals that "about 13,000 prisoners have been executed at the government-run Saydnaya prison near the capital, Damascus".

Between 2011 and 2015, the report states, groups of at least 50 inmates at Saydnaya prison were taken out of their cells every week, beaten and then hanged in the middle of the night in "utmost secrecy".

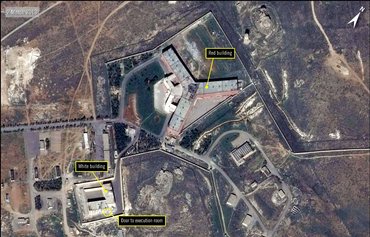

![An aerial photograph of Saydnaya prison in Syria. [Amnesty International]](/cnmi_am/images/2017/02/20/7280-aerialphoto-600_384.jpg)

An aerial photograph of Saydnaya prison in Syria. [Amnesty International]

![Emaciated men pictured inside Saydnaya prison in Syria. A recent report states groups of at least 50 inmates in the prison were taken out of their cells every week, beaten and then hanged in the middle of the night. [Photo from the archive of Bashir al-Bassam]](/cnmi_am/images/2017/02/20/7281-emaciated-600_384.jpg)

Emaciated men pictured inside Saydnaya prison in Syria. A recent report states groups of at least 50 inmates in the prison were taken out of their cells every week, beaten and then hanged in the middle of the night. [Photo from the archive of Bashir al-Bassam]

The report also accuses Syrian President Bashar al-Assad of pursuing a policy of "extermination" in prisons with the mass execution of inmates, noting that most of those who were hanged were civilians opposed to his rule.

Amnesty said that such practices constitute "war crimes and crimes against humanity" and pointed out that they are likely continuing to occur.

Al-Assad dismissed the report in a February 10th interview, saying it was "definitely not true".

'The worst kinds of torture'

Omar al-Saad a former prisoner at Saydnaya who asked to use a pseudonym out of fear for his safety, told Diyaruna he was arrested in Damascus on March 10, 2011 by Syrian intelligence forces who were deployed in the streets.

The round-up of protesters began after demonstrations started in Syria, he said.

Al-Saad said he was interrogated at a security centre where he remained for a week, during which time he was subjected "to the worst kinds of torture".

He was charged with being a "terrorist" and providing information to "armed terrorists coming from Iraq", he said, though he claims he had no involvement in politics and was devoted full time to his work as a tradesman.

"I was transferred to Saydnaya prison, where I spent close to [three] months," he said, describing that period as "lifeless".

Al-Saad said most prisoners were tortured on a daily basis, especially new arrivals who were detained after the start of the Syrian revolution.

"The jailers subjected the prisoners to various kinds of torture and beat them around the clock," he said. "Life had no value for them and death was present at all times, as every hour or so, news spread of a prisoner dying from torture or an announcement was made of his execution."

Dozens of prisoners died during the time of his detention, he said, "either directly by execution or due to severe torture".

On the evening of June 4, 2011, al-Saad said he was told he would be released the next day.

He was released as part of a large group, he said, "as the regime periodically released a group of detainees to on one hand calm the situation somewhat, and on the other cover up the executions".

"After the torture I was subjected to in Saydnaya and the horrors I witnessed and experienced, I decided to leave Syria," he said. "I fled to Lebanon with my family and from there to Egypt, where I still am to this day."

Falsified records

Syrian lawyer Bashir al-Bassam, who resides in Cairo, told Diyaruna he lost his brother and cousin after they were imprisoned in Damascus in 2012.

"The crimes [perpetrated] in detention centres have been proven and the new report is but further proof of the criminality of the regime’s agencies," he said.

After his brother and cousin were arrested, he said, "there was no news of them for several months, until I received news of their death during detention and burial at an unknown location".

It later transpired they had been transferred to Saydnaya prison, he said, where they were killed after being interrogated at a Damascus security agency branch.

"Information received from regime areas and reliable human rights sources state that the regime, to conceal its crimes, announces every now and then the release of a fictitious number of detainees to absolve itself of responsibility," al-Bassam said.

"The detainee loses his life, while in the records he is listed as having been released, and thus becomes ‘missing in the war’," he added.

The regime’s agencies systematically fabricate charges, he said. Prisoners are listed as criminal detainees, and many are accused of spying, murder or some other crime whose maximum penalty is death by execution.

These executions are carried out after sham trials, he said.

This is not the first time the regime has been implicated in prison executions, he said, as in September 1980 Amnesty International confirmed that up to 1,000 political detainees had been executed in the Tadmor (Palmyra) military prison.

'Return from hell'

Ali Abu Dehn, a native of south Lebanon, told Diyaruna he was arrested in Syria on December 28th, 1987, and released on December 15th, 2000, after serving the last part of his sentence in Saydnaya prison.

"Saydnaya prison has a notorious reputation for the numerous abuses, brutal acts of torture and systematic killings that take place in it," he said.

"The overcrowding of detainees in one room is unacceptable by any logic or human standard. Dozens, rather hundreds of detainees are placed in one cell with an awful floor without food, drink or medicine," he said.

He described Amnesty's report as "a call to every conscience in the world".

Abu Dehn is active in campaigns that seek the release of inmates from Syrian prisons, and has documented his own detention and torture in a book, play and movie.

"When I came out of prison, I decided to write about what happened to me in detail and resolved to expose the brutal methods used in the Syrian regime’s detention centres by writing my memoirs," he said.

His book, "Return from Hell - Memories of Tadmor (Palmyra) and its Sisters", was published in 2012 and details the physical torture and psychological anguish he and other detainees suffered and their lingering ill effects, he said.

A 2016 movie based on this account, "Tadmor", was produced in collaboration with the Association of Lebanese Detainees in Syria, starring former Lebanese detainees and co-directed by Monika Borgmann and Lokman Slim.

His play, "The German Chair", also shows life in Syrian prisons, he said, adding that the title was inspired by one of the commonly used torture methods, which was so excruciating that its use resulted in breaking the prisoner’s backbone.

Crimes against humanity

Under Syria's 1979 penal code, death sentences are to be commuted to life imprisonment if the offender was convicted of a political offense.

However, this has not been happening, and Syria continues to apply the death penalty in these cases, Regional Centre for Strategic Studies researcher and Cairo University criminal law professor Wael al-Sharimi told Diyaruna.

"The regime resorts to fabricating charges that have a maximum penalty of death by execution to create a legal loophole for its criminal acts against civilians opposed to its policy and those considered to be political prisoners," he said.

The torture and killing of political prisoners is considered a crime against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, he said.

"Crimes against humanity are tried before the International Court of Justice in the Hague," he said, adding that the Syrian regime should be held to account for its actions, which clearly violate international law.

![Inmates reach through the bars at Saydnaya prison in Syria. An Amnesty International report revealed the Syrian regime has executed 13,000 detainees since 2011. [Photo from the archive of Bashir al-Bassam]](/cnmi_am/images/2017/02/20/7279-saydnaya-600_384.jpg)