CAIRO -- Syrians have widely dismissed Bashar al-Assad's highly-publicised pardoning of political prisoners, some of whom have been incarcerated in the regime's notorious prisons for close to a decade, as a cynical publicity stunt.

After the regime announced it was releasing "hundreds" of prisoners during a mass amnesty on Eid al-Fitr, dozens of families waited anxiously in the centre of Damascus to see if their loved ones would be among those released.

Many took part in an overnight vigil, displaying photographs of their relatives and holding out hopes that they might be among those to be safely returned.

Many were disappointed.

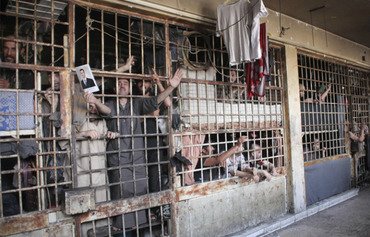

![Detainees released by presidential pardon are seen at a government building in Damascus province, beneath a photo of Bashar al-Assad. Many Syrians accuse the regime of using the amnesty as a publicity stunt. [Facebook]](/cnmi_am/images/2022/05/17/35348-syria-released-prisoners-600_384.jpg)

Detainees released by presidential pardon are seen at a government building in Damascus province, beneath a photo of Bashar al-Assad. Many Syrians accuse the regime of using the amnesty as a publicity stunt. [Facebook]

The precise number of pardoned prisoners is unclear, but activists said it was a small number compared to the total prisoner count in Syria.

Initial reports showed a batch of 60 prisoners had been released, and Syrian activists shared a list of 20 released detainees on social media, including people who had wasted away for years in the notorious Saydnaya prison.

Al-Assad issued a decree granting "general amnesty for terrorist crimes committed by Syrians" before April 30, 2022, "excluding crimes that led to the death of human beings, as stipulated by the counter-terrorism law".

This would mean that tens of thousands could be released, said Syrian Observatory for Human Rights head Rami Abdel Rahman, noting that "terrorism offenses" is "a loose label used to convict those who are arbitrarily arrested".

But so far very few have tasted freedom.

According to a number of Syrians who spoke to Al-Mashareq, many prisoners who were simply critical of or opposed to the Syrian regime remain imprisoned.

They described the pardons as "a farce".

The highly publicised decree and token release of prisoners is merely an attempt by al-Assad to clear up his image and cover up the regime's harsh treatment of prisoners, they said.

Al-Assad's ally, Iranian leader Ali Khamenei, in a recent and rare visit by the Syrian president to Iran, publicly praised him despite fresh war crime allegations against him.

By some estimates, Iran has deployed thousands of soldiers to fight alongside the Syrian regime's military forces. These include militias trained and armed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps' Quds Force (IRGC-QF).

Khamenei noted the IRGC-QF's role in helping al-Assad carry on the war against his own people, and cited Qassem Soleimani, the late IRGC-QF commander, as "one of the instrumental reasons for Syria's victory in the war".

'At least 200,000 imprisoned'

"Thousands of Syrian families are still waiting for their sons to be released from the regime's prisons, and there are many gatherings of family members near prisons," Damascus-area activist Muhammad al-Beik told Al-Mashareq.

The number of released prisoners is in the hundreds, he said, noting that this is just a small percentage of the total number of those who were detained or forcibly disappeared.

The detainees' families have been in a state of deep anguish, he said, as the prisoners were pardoned arbitrarily, and the families were not notified about about which inmates were to be released during the amnesty.

Due to the lack of communication with families, some released prisoners had to make their own way home, as their families were unaware of their release, al-Beik said.

The regime still has not released a list of the names of pardoned prisoners, he added, estimating that its security apparatus has detained at least 200,000 Syrians since 2011.

He described the presidential decree as largely meaningless, noting that thousands of families still do not have any news of relatives who remain incarcerated in the regime's prisons.

He also accused the Syrian regime of attempting to use the amnesty declaration as a form of propaganda, spreading the news in affiliated media and through various social media accounts in a way to boost its image.

Image-burnishing propaganda

According to Jumaa al-Masalmeh, an independent activist from Daraa, the regime is using the prisoners' release as part of an image-burnishing propaganda campaign.

Its media coverage is particularly targeting areas where residents are strongly opposed to the regime, such as Daraa and rural Damascus, he said.

"In Daraa, for example, only a few dozen prisoners were released, while the number of detainees is in the hundreds," he said.

"Everyone remains silent for fear of retribution against those they hope are [alive and] still in detention."

Al-Masalmeh said the timing of the presidential pardons has served al-Assad well in Daraa, after recent tension there between residents and the regime's security apparatus.

People in Daraa have kept calm mainly out of fear of the regime's retaliation, he explained, as they are concerned that their relatives might not be released if they protest against the regime.

Syrian lawyer Bashir al-Bassam said the presidential pardon was announced immediately after a video that showed prisoners being executed was widely circulated on social media.

With the decree, he said, the regime intended to obfuscate the video and draw attention away from its years of violating prisoners' rights.

The Syrian regime's executions, particularly those carried out during the early years of the conflict, were carried out in an arbitrary manner, al-Bassam said.

"Officers, soldiers, and elements of regime-affiliated militias carried out the executions," he said.

The regime's propaganda campaign, which has been particularly active on social media of late, undoubtedly aims to inflate the number of those released in order to draw attention away from its crimes, he said.

Fresh evidence of the regime's brutal treatment of prisoners continues to come to light.

In a recent report on two mass graves discovered outside Damascus, eyewitnesses to the burial reported seeing signs of torture on the corpses arriving at the site from nearby Saydnaya prison.

![The family members of imprisoned Syrians hold a vigil in central Damascus after the announcement of a presidential pardon. Many waited for their loved ones in vain. [Twitter]](/cnmi_am/images/2022/05/17/35349-syria-amnesty-families-600_384.jpg)